Threat Research

Pure Extraction: Ransomware Groups Prioritize Data Theft

New threat intelligence from At-Bay reveals a 450% increase in non-encryption-based attacks between Q3 and Q4 2025 and explores how an emerging ransomware group is weaponizing legitimate IT tools to steal data without ever deploying ransomware.

The cybersecurity industry has spent years focusing on ransomware encryption as the primary threat, developing detection capabilities and recovery strategies centered on identifying malicious encryption activity.

However, new incident response data from At-Bay Security reveals a massive 450% surge in non-encryption-based attacks between Q3 and Q4 2025. While traditional ransomware “locks the door” and leaves a note, At-Bay is seeing an evident shift toward “pure extraction,” where attackers skip the encryption entirely to stay under the radar, focusing instead on the quiet theft of sensitive data.

In the latter half of 2025, a number of new ransomware groups published leak sites, many of them prioritizing data extraction over encryption. One group goes by the acronym PEAR (Pure Extraction and Ransom) Team and has been observed by the At-Bay Response & Recovery team successfully exfiltrating terabytes of sensitive data.

Examples of other emerging groups using this method include the likes of Genesis, Kyber, Coinbase Cartel, and Radiant, while established groups like ShinyHunters and Clop continue to pull off lucrative heists with it as well.

In the following analysis, At-Bay unpacks the statistics, tactics, and techniques that the new ransomware group – PEAR – is using to extort businesses in the US.

PEAR Group Facts & Key Stats

- First Detected: June 2025

- Total Victim Count (from leak site): 51 (from leak site)

- Primary Industry Targets: A variety of industries, with the top being healthcare, business services, manufacturing and technology.

- Regions: Notable focus on US-based entities

- Strategy: Data broker / extortion without confirmed encryption

- Average Ransom Demand (At-Bay Observations): Approximately $550,000

Tactics, Techniques, and Targets

Skipping Encryption, Maximizing Pressure

Unlike traditional ransomware groups that encrypt files and demand payment for decryption keys, PEAR operates exclusively through data theft and public shaming. The group exfiltrates sensitive data, posts victim names to its Tor-based leak site, and threatens staged releases of stolen information.

This model offers threat actors several advantages. Encrypting victims requires access to software that can effectively lock victim files and a decryptor that can unlock them. While some ransomware lockers may be found publicly available on underground forums, building a custom locker requires developer expertise. Using an exfiltration-only model lowers the bar to enter the cyber extortion space for threat actors without specific technical expertise, who can build and maintain their own locker. It also lowers other risks. For example, without encryption, there’s no technical failure point — no decryptor that might not work, no recovery complications. The attack also generates less immediate noise in a network, allowing threat actors to maintain access longer before victims realize they’ve been compromised.

In one instance, the At-Bay Security team identified evidence of a threat actor having network access for approximately six months. While it was unclear if it was the PEAR group that maintained access the entire time, it was the PEAR team who reached out to extort the victim for data theft. Prior to this notification, the victim was unaware of any network issues. In this case, a threat actor compromised the initial account in mid-February 2025, but large-scale exfiltration didn’t start until mid-August, giving the threat actor(s) ample time to map the network, identify valuable data, and establish multiple persistence mechanisms.

Harassment as a Negotiation Tactic

PEAR distinguishes itself through aggressive victim communication. Unlike groups that rely solely on ransom notes or dark web contact forms, PEAR sends direct text messages and WhatsApp communications to company employees, claiming to have stolen terabytes of data.

This direct contact serves multiple purposes. It creates immediate psychological pressure, bypassing IT security teams to reach decision-makers directly. It also establishes a sense of urgency before victims can fully assess the scope of the breach or gather forensic evidence.

The group maintains strict deadlines, demands daily check-ins during negotiations, and offers minimal discounting of typically around 10% for rapid payment. Perhaps most notably, PEAR lists victims on its leak site early in the negotiation process, using public exposure as ongoing leverage rather than a final consequence.

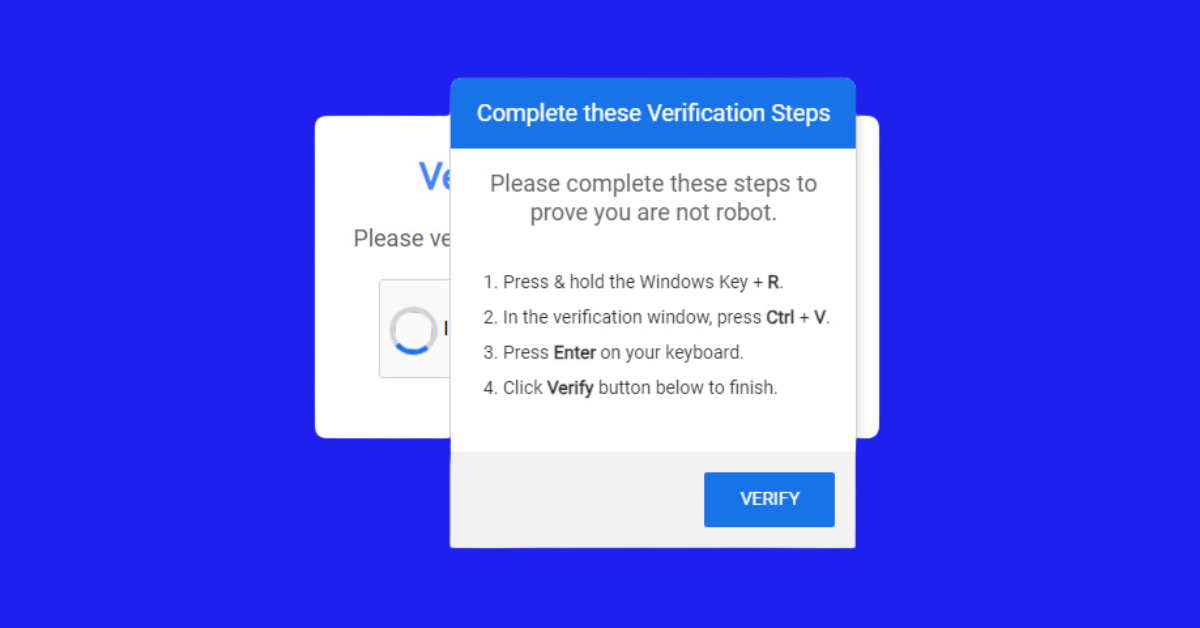

Living Off the Land: The Security Blind Spot

PEAR relies on legitimate administrative tools to conduct nearly every phase of the attack, making detection difficult. At-Bay’s incident response work identified a consistent toolkit across multiple intrusions:

For Initial Access: Compromised VPN credentials, likely obtained through previous breaches or credential-stuffing attacks, provide the entry point. In the cases examined, threat actors connected through the organization’s Virtual Private Network using valid user accounts.

For Persistence: Rather than installing custom malware, PEAR deploys legitimate remote management tools like AteraAgent and Splashtop Remote Service. These applications are designed for IT support and are commonly whitelisted by security software, making malicious use difficult to distinguish from legitimate administrative activity.

For Credential Harvesting: The group uses well-known tools like PsExec for remote execution and credential dumping utilities to extract passwords from memory. While security software often flags these activities, the threat actors simply persist, returning repeatedly even after blocks.

For Data Exfiltration: PEAR relies on file transfer applications like WinSCP and RClone (frequently renamed to evade detection) to move data out of victim networks. In one incident, forensic analysis revealed that approximately 732 gigabytes of data were transferred to external infrastructure over a 24-hour period using WinSCP.

This “living off the land” approach creates a detection dilemma for defenders. Every tool PEAR uses has legitimate administrative purposes. Security teams can’t simply block PsExec or WinSCP without disrupting their own operations. Even when security software detects and blocks specific malicious uses, threat actors can modify their approach slightly and try again.

Targeting Organizations Across All Sizes

PEAR targets organizations ranging from small businesses to enterprises with over $1 billion in revenue, though the majority of victims are smaller organizations. The group focuses particularly on professional services, healthcare, manufacturing, and government sectors. Based on At-Bay’s engagement data, initial ransom demands average around $550,000. For small and mid-sized businesses, a half-million-dollar extortion demand can represent an existential threat.

Observations & Learnings

When Detection Isn’t Prevention

In the longer-running intrusion, Microsoft Defender and SentinelOne flagged and blocked credential dumping attempts repeatedly between March and September 2025, yet the threat actor maintained access.

The forensic evidence shows a clear pattern: security software would detect malicious activity, block the specific attempt, and generate an alert. The threat actor would wait, then try a different variation of the same technique. Over time, they successfully harvested credentials, moved laterally across the network, established remote access tools, and exfiltrated hundreds of gigabytes of data.

This persistence highlights a critical gap in many security programs. Detection and blocking individual malicious actions doesn’t equal containment if the underlying access vector remains open. Threat actors who gain initial access through compromised VPN credentials can continue returning to the network as long as those credentials remain valid.

Rethinking Defense Strategies

The PEAR threat actor model challenges several common assumptions about ransomware defense:

Assumption 1: Advanced malware detection is the primary defense need.

Reality: When threat actors use legitimate tools, malware detection becomes less relevant. The focus must shift to anomalous behavior detection, unusual use of admin tools, and understanding what normal administrative activity looks like.

Assumption 2: Legacy VPN infrastructure is adequately monitored.

Reality: In the PEAR incidents observed, the initial compromise occurred through VPN access, yet the specific accounts used to gain initial entry weren’t identified due to insufficient logging. Organizations often have robust logging for cloud applications and endpoints but maintain minimal visibility into older remote access infrastructure.

Assumption 3: Detecting malicious activity is sufficient.

Reality: Detection must be coupled with a thorough investigation and rapid containment. Blocking individual malicious actions while leaving the access vector open simply forces threat actors to try alternative approaches, which they consistently do. Further investigation should always be conducted when reviewing security logs and alerts with anomalous activity to ensure the root cause is addressed.

Assumption 4: Backup and recovery planning should focus on ransomware encryption.

Reality: Pure extraction attacks require different response considerations. Organizations must plan for scenarios where data integrity isn’t compromised but confidentiality is, requiring breach notification, regulatory response, and reputation management rather than technical recovery.

The Broader Implication

PEAR represents one example of a broader trend in cybercrime: the professionalization and specialization of extraction operations. By eliminating encryption from their operational model, these groups reduce the technical sophistication needed to enter the cyber extortion space while maintaining significant leverage over victims. By weaponizing legitimate tools, they evade security controls and blend into normal network activity.

The extended dwell times, like the one observed in the intrusion above, indicate that victims often don’t realize they’re compromised until threat actors announce their presence. This announcement may come in the form of a reachout by the threat actor, a posting online, or through the identification of encrypted files and inaccessible systems. This suggests that traditional indicators of compromise may be insufficient when attackers use approved tools in unapproved ways.

For security teams, the challenge is clear: effective defense requires not just detecting what’s obviously malicious, but understanding what’s subtly wrong. When the threat actor’s toolkit looks identical to the IT administrator’s toolkit, context becomes everything. Was that credential dump part of a planned migration, or unauthorized reconnaissance? Is that WinSCP transfer a legitimate backup, or data exfiltration?

These questions require security programs that emphasize behavioral baselines, continuous monitoring, rapid response to anomalies, and most importantly, the elimination of persistent access vectors when suspicious activity is detected. Blocking the action without closing the door simply invites the threat actor to knock again, as PEAR has demonstrated repeatedly.